Discerning with dust

November 9, 2016

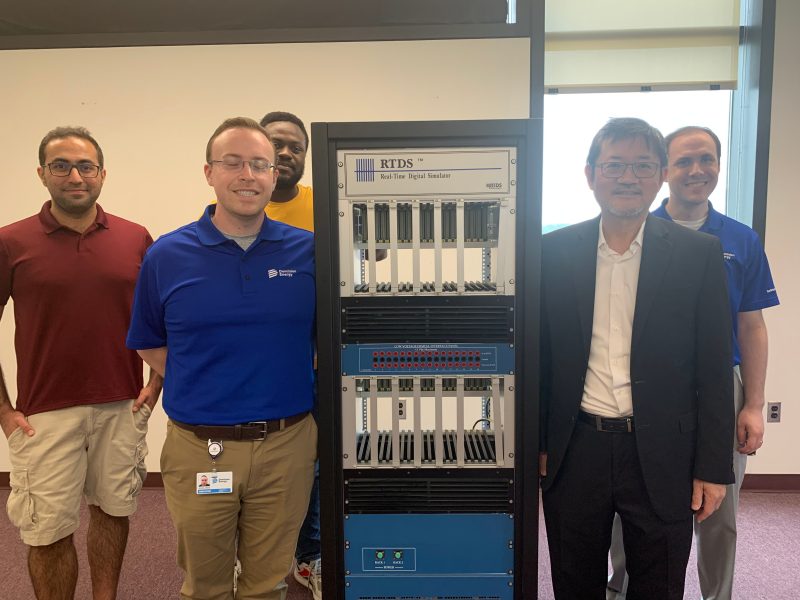

Wayne Scales is studying atmospheric dust, which can also be created by sounding rockets like this one.

As humans, we constantly sense our environment, and make decisions based on what we notice. We taste something bitter and stop eating it. We smell pungency and move away from it. We hear thunder and get out of a swimming pool. We feel a strong wind and work to protect crops and houses. We see a tornado and take cover. But there is weather the human body cannot sense, and ECE's Wayne Scales is helping us to understand how it impacts our world and our technology.

Artificial dust clouds, like the one pictured here from Scales' Charged Aerosol Release Experiment in 2009, can help researchers understand how the atmosphere reacts to disturbances.

Space weather can follow similar patterns to the weather on the earth's surface, but is too distant to observe without specialized equipment. However, it can affect our environment and disrupt our technology, particularly communications devices, such as GPS satellites. Scales and his team are working to understand why by studying the microphysics of the space environment.

To better understand processes in our environment, researchers actually stimulate the upper atmosphere by generating waves and turbulence either from the ground, by using high power radio waves, or by releasing chemicals, aerosols, dust, or charged particles from spacecraft. They then observe and measure how the environment reacts.

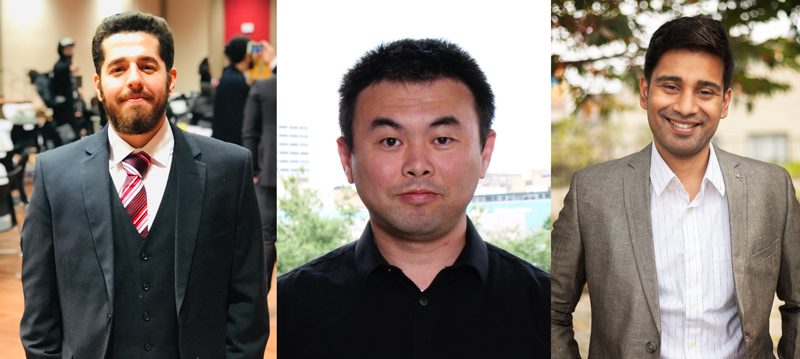

Scales uses the High Frequency Active Auroral Research Program facility in Alaska (left) and the European Incoherent Scatter Radar facility near Troms, Norway (right) to conduct some of his active experiments.

Their ground-based experiments use the High Frequency Active Auroral Research Program (HAARP) facility in Alaska. "It's the most powerful ground-based transmitter of its type in the world," explains Scales, and "it can produce 3 billion Watts of effective radiated power." He also performs experiments at the European Incoherent Scatter Radar (EISCAT) facility near Troms, Norway, another premiere active space experiment facility.

One of Scales' active experiments is to heat the natural dust layer that surrounds the earth. This dust layer is caused by meteor ablations, or the soot released when meteors burn up in the atmosphere, explains Scales. "The visual manifestation of this is noctilucent clouds," he continues, which are also called polar-mesospheric clouds when they are observed in space. "Scientists think these might be related to climate change." These clouds were first observed in the 1880s, and their frequency has been increasing since then, possibly linked to human activity, according to Scales.

Using high-powered radio waves, researchers can heat these clouds and study the response of the associated turbulence using radar echoes. Scales has developed a model that can use these measurements to determine the size of the dust particles, their charge state, and their location. "We look at how the clouds evolve, how the dust particles are formed, how they grow, and the sedimentation of the particles. Once that's understood, we can look at a global picture and see if this is related to global climate change," he explains. "Active experiments like these give us initial conditions to more effectively study the physics and chemistry of the space environment," says Scales, which provide a better understanding of its impact on critical technologies.

"Ten years ago, this model was just theoretical," Scales notes. When he was developing the model, the results seemed unphysical, according to Scales. "I tried to step back and look at it from a fundamental physics standpoint, but it took me a while to justify it." He was eventually able to prove that the results were based on the physics, and were not just an artifact of the model. "A decade after I developed the model, it was finally validated. I think that's one of the most exciting things for a scientist who does theoretical modelingto have your work validated by experiment."

"As humans, we always have to assess our surroundings, and the space environment is part of our surrounding environment," says Scales. Whether the effect of turbulence in space is harming our communications or actually a precursor of global change, he and his fellow researchers are helping us understand exotic natural phenomena that have significant impact on our daily lives.