A closer look: Improving fertilization outcomes with imaging

November 9, 2016

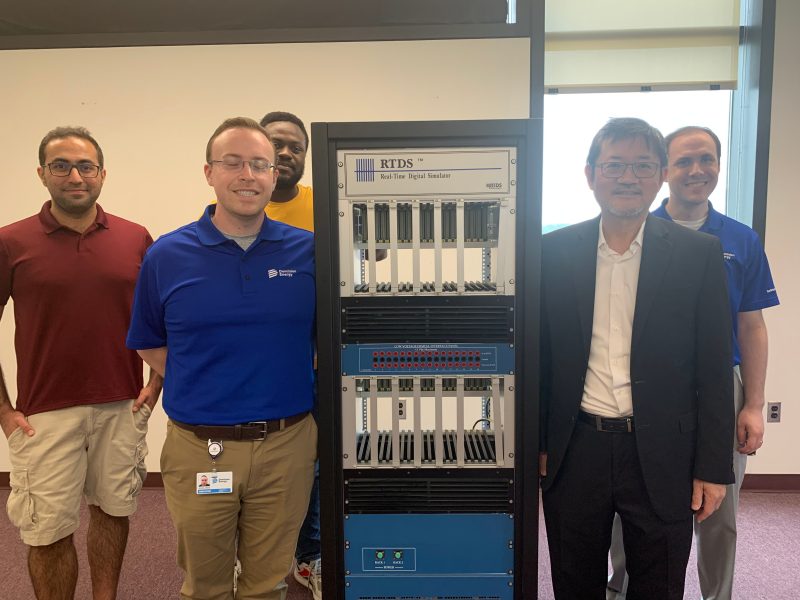

Yizheng Zhu is looking at the morphology of sperm, eggs, and embryos, creating images like the one above to help improve outcomes for in vitro fertilization.

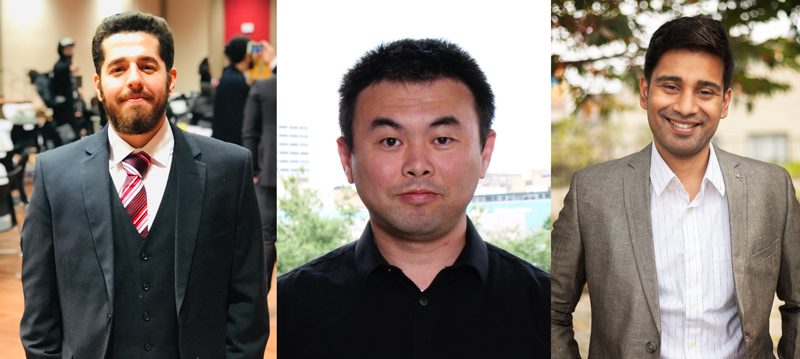

Infertility affects more than 10 percent of the population, and in vitro fertilization (IVF) is the primary treatment. Although more than 300,000 births worldwide are the result of IVF each year, the success rates are low, making the process emotional, time-consuming, and expensive, according to Yizheng Zhu, an assistant professor in ECE.

Zhu hopes to improve success rates and reduce cost by creating better imaging technology. With better and less expensive imaging, doctors could quickly ensure that the most viable sperm, eggs, and embryos are used.

IVF typically involves removing eggs from a woman, fertilizing them in a laboratory with sperm, and implanting multiple fertilized eggs into the woman's uterus, hoping that one or more will lead to pregnancy. According to Zhu, a couple will have to go through this process an average of three times to succeed once. "Couples go through an emotional rollercoaster, and it involves a lot of physical and financial stresses," Zhu says. "We're developing a special optical microscope to assess the quality of sperm cells and embryos, which we hope will improve the success rate."

Zhu's research focuses on developing fiber-optic-based technology to image specimens that range in size between nano scale and nearly visible. "We develop techniques that can help the treatment or diagnosis of diseases by using optical imaging technologies," he explains.

Each part of in vitro fertilization, sperm, eggs, and embryos, requires different imaging techniques. Yizheng Zhu is creating a platform that can use many of the same components to image all three.

He uses the intrinsic properties of specimens, such as thickness and density, to detect light in a non-fluorescence way. He focuses on morphology and detecting the tiny changes between an object and its surroundings.

Imaging plays an important role in determining the quality of sperm, eggs, and embryos, Zhu explains. The imaging challenge is complicated by the need for different techniques to image these specimens. "We're trying to develop an integrated, shared platform that can do all three kinds of imaging with the same equipment," says Zhu. "The cost will go down and the usability will be increased." His team has already developed the different techniques needed, and have promising preliminary results. "The next step is to integrate them. There is great potential," says Zhu. The three systems share many components, including the light source and the detector, making integration possible.

Sperm cells can be particularly difficult to image, Zhu explains, because they move at high speeds. "A lot of current technologies can't keep up with sperm cells, or their quality is not great. You need high sensitivity to capture the details of morphology the form." Zhu has developed a system to capture this detail at acceptable speed.

"The next step is to study how morphology is related to the quality of the sperm cell," he says, and he is specifically looking at the sperm heads. "Because of the special organization of DNA inside the head, light oscillates in different directions and travels at different speeds," says Zhu. "The integrity can be related to this anisotropic behavior called birefringence." Birefringence occurs when light travels at different speeds depending on the direction of oscillation. By measuring birefringence, Zhu can estimate the quantity and quality of the DNA in the sperm head.

Because this research is at an early stage, Zhu's team is currently working with samples from pigs and cows. Once they prove the process works, they can proceed to human testing. Eventually, Zhu envisions IVF imaging becoming an automatic process, with samples flowing through microfluidic channels while being analyzed and selected by a computer. "These are very sensitive samples that don't usually live outside the human body, so you want to keep them in a friendly environment with minimal human interference," says Zhu.